Some Movies Were Made To Be Felt…

Imagine a brazen stretch of nothing as far as your eyes can see, as if awaiting the very beginning of the world itself, as apes and tapirs struggle amongst themselves for sustenance. You are inside a dark theatre, as the scenes break into nervous trepidation, fear, glee, and loud noise, noise ensuing from the fear of being gnawed away against the backdrop of a blue sky, rocks piled upon, and a land bereft of vegetation. What 2001: Space Odyssey creates with the brilliant usage of a 70mm aperture is riveting, and would perhaps remain as the best technique to produce its grandeur further accentuated by the background score Thus Spoke Zarathustra.

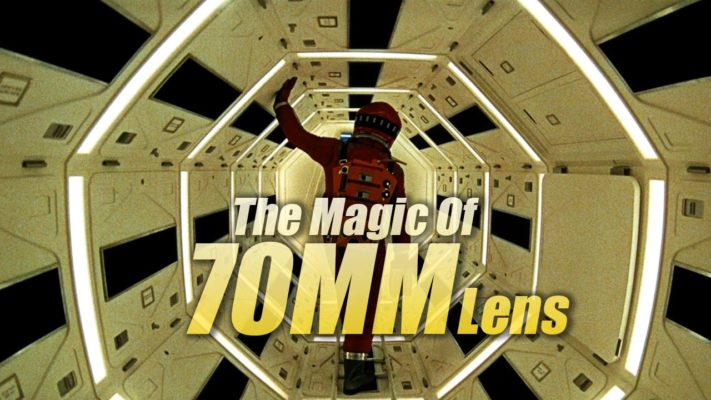

Today, the film is regarded as Stanley Kubrick’s magnum opus synonymous with the brilliance of 70mm lens recorded in the history of motion pictures. The post will reminisce about the visual experience of 70mm aperture in cinema, its history and significance and why some of the best directors decided to return to the majesty of 70mm lens.

2001: Space Odyssey

In the history of motion picture, I personally believe that 70mm was unparalleled in capturing movements and stillness of the film. Space Odyssey clearly plays with the notion of speed and movement, especially in the sequence when we are racing into what appeared like a psychedelic array of bright neon colours, as the colours filter through Dave Bowman’s eyes. The brilliant cinematography helps the audience to grasp the bewilderment of Dave Bowman, who is yet to figure out a way of securing communication with Earth. In the film, 70mm resolution lends a density to plethora of colours, starting from the serene sky juxtaposed with a desolate looking land, to bright and apathetic eye of HAL 9000 computer, to the soothing infinity of night, and again back to the crass red colour lining the insides of HAL 9000.

The sound effect delivering a spooky blend of breathing and pleadings from HAL 9000 produce the mental image of helpless claustrophobia with the wider aspect ratio of 70mm film format. If cinema can be taken as more of an experience, a journey rather than a visual treat, then 2001: Space Odyssey is the finest example. 70 mm has rendered scenes to appeal to the imagination., For instance, the lens zooming into the eyes of the murderous machine, its voice reverberating within the theatre ensuing a surge of terror. The sharper edges of this resolution take us to a different journey that defies gravity, and prevalent concept of time and finite, each scene more invigorating than its predecessor.

Hamlet (1996)

Directed by Kenneth Branagh, the sharpness of each scene is a harrowing exposition of fear, suspense, paranoia, agitation, and madness of one of the most renowned Shakespearean tragedies of all time. With Hamlet, the prowess of 70mm does justice to the longest adaptation of the Shakespearean tragedy on screen. The towering figure of King Hamlet in the very opening scene sets the tone for the rest of the play. it is filled with imposing anticipation, manic restlessness, and an alarming fright that many of the characters will be subjected to.

Remember the mousetrap scene in Hamlet? The wider resolution at once letting us delve into the perspective of different people who are watching over the king, Horatio, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern among the others. We see the Mousetrap play from different angles, which was an essential to bring forth the importance of staging the play in front of the royal members sitting as audience.

70mm Is An Experience In Itself

70mm was most recently used in Dunkirk by Christopher Nolan, taking the audiences into the middle of a catastrophe with colourful and vibrant background inadvertently passive to war brutalities. With most of the films today, available on the we, immediate or before their release, cinema-making has lost much of its grandeur. Earlier, scenes were meant to be lived in the cosiness of dark theatre rooms, with the camera zooming in and out, the experience was far more real than any screen resolution a smartphone could offer.

With sharper edges and wider angles, films like Lolita and Exodus were meant to alter the perception of audiences towards cinema as an art. In Exodus, by Otto Preminger, and Lawrence of Arabia the former a historical drama based on T.E Lawrence while the later has its theme rooted in the founding of Israel were shot considering abundance of their minute details.

Pompous desert scenes in Lawrence of Arabia where Jon Box portrayed a mirage creating an impression of the sea in the middle of the desert, were delivered in square footage that 70mm allowed for it to bring alive the character of Lawrence and Omar Sharif to audiences. In Dunkirk, in the beach-bombing scene where thousands of soldiers were scattered like ants waiting to be rescued, and can be savoured the best in a theatre hall imperative to realize the pricking monstrosity of war that Nolan makes us see from his panorama. 70mm is therefore not just another resolution that the directors have experimented with in the past to offer the audience both a very cinematic and immersive experience but a revolutionary decision amidst issues like lengthier processing time, surging maintenance costs of making a movie with 70mm and popularity of digital projection system that have made the 70mm less frequent.

With time, embellished images and mind-boggling visuals of cinema are fading away as 70mm lens is falling out of use, its use confined to the nostalgia of watching Dead Poets Society, Lethal Weapon 2 and Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, time and again.