Where It All Began

South India, and more precisely Kerala, has been leading the front in terms of political cartooning since 1919, even though Kerala was not the first Indian state to have shown interest in the art form. In fact, it was the British satire magazine ‘Punch’ that worked as an inspiration for India to take up the form of cartooning as a means of political expression.

‘Punch’ successfully inspired the creation of ‘Parsee Punch’ and ‘Oudh Punch’ in 1854 and 1877 respectively. While ‘Parsee Punch’ delivered its sharp-witted political humour in the Parsi Gujarati language, ‘Oudh Punch’ served the same purpose in Urdu. Moreover, the Tamil journalist, poet and activist, Subramania Bharati, launched cartoons in the extremist political journal, ‘Indian’, of which he was the editor. However, whatever the roots of political cartooning might have been for India, Kerala became its home.

Kerala And The Unapologetic Art Form Of Political Cartooning

‘Mahakshamadevatha’ meaning “The God of Famine”, came to be known as the first cartoon that was published, however, unsigned, in the state of Kerala. It was published in the monthly humour magazine called ‘Vidooshakan’, or “The Jester”, in 1919 in the month of October in Kollam. One of the most popular scenes from the ‘Mahakshamadevatha’ that grabbed massive public attention shows a formidable superhuman structure supervising over a torture, starvation and death scene at the cartoon frame’s centre.

The left hand of this figure is shown holding a spear on which rests a dead human that has been pierced through. The right hand of this superhuman godly creature is shown holding a petrified figure struggling and fighting to escape a fate similar to the one on the spear. Finally, there is shown standing a man of authority (who is obviously smaller than the godly figure), dressed in Western clothes– cap, cape, trousers and boots –with his hands lifted up in blessing or authorization, completely unaffected by the macabre frivolities going on.

According to Bonny Thomas, a former cartoonist and author at the Economic Times, who came across ‘Mahakshamadevatha’ in 1989 at the State Central Library in Thiruvananthapuram, the scenes of the cartoon brilliantly expresses a powerful view that stands against colonialism and war.

While talking about the scene from the cartoon described above, he said, “It was the end of World War I, many parts of Kerala were facing famine because of rice shortages. The Travancore king had introduced tapioca cultivation to keep off a crisis –you can see the plant in the margins. The Englishman, likely a policeman or an army man and a representative of colonial powers, is blessing the durdevatha or malevolent god, and the destruction he was causing.”

The Rise Of Indian Cartoonists

Although ‘Mahakshamadevatha’ undoubtedly drew its inspiration from the British magazine, ‘Punch’, cartooning began to seep deeper and deeper within the layers of political satire in Kerala within the next decade. Kerala began to produce cartoonists who gained popularity in the blink of an eye, in Malayalam magazines and newspapers. The state flourished with cartoon enthusiasts and cartoonists who became legends and were delegated with responsibilities in both national as well as international publications.

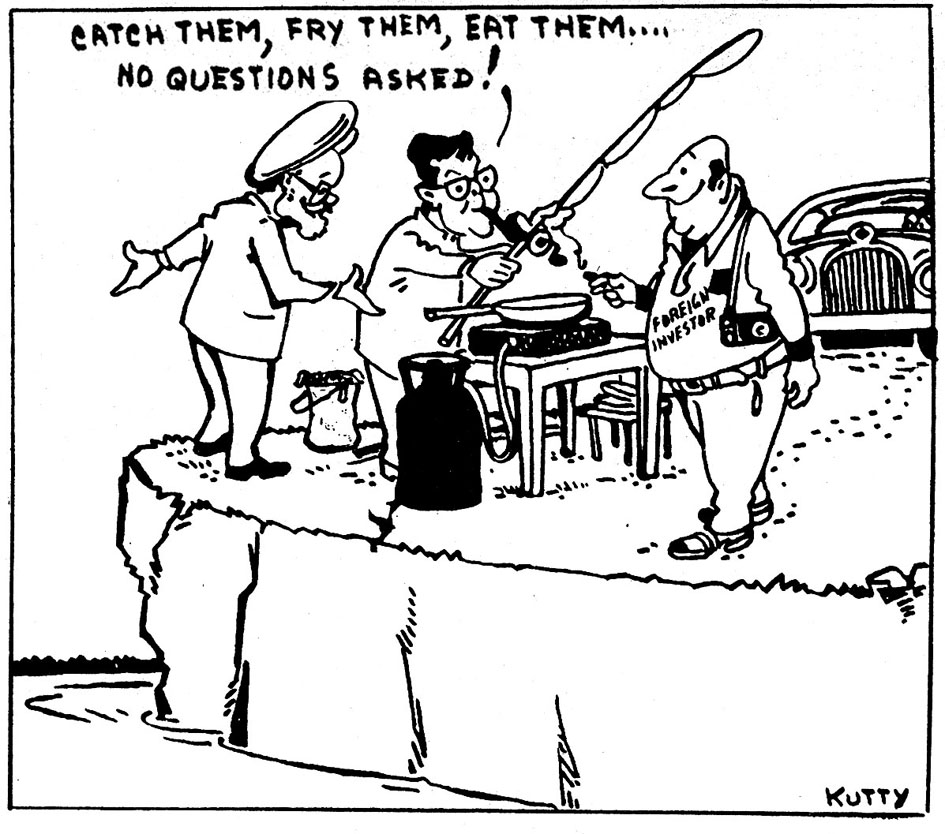

P.K.S Kutty is one such exported legend who had even spent time working at the popular Bengali newspaper ‘Anandabazar Patrika’.

E.P Unny, a cartoonist for Indian Express, expressed his pride for Kerala’s cartooning tradition in a celebratory article for the cartooning centenary of Kerala in the Malayalam literary magazine, ‘Bhashaposhini’ published by the infamous ‘Malayala Manorama’ –“Almost every newspaper in Kerala has a front page cartoon and sometimes inside as well. Even in Europe, you will not find the art this prolifically visible every single day. Three crore people, 100% literacy, three in five a newspaper reader, three out of four a voter. And Cartoons everywhere.”

Humour, Irony, Politics And The Talk

The South’s proclivity towards satire is inherent and ancient, it goes back almost 1500 years. Keeping up with such an ancient tendency, satire is all over the entertainment and media industry in Southern India. The popularly known “mimics parade” are famous for their parodies and imitations of celebrities and politicians. The political burlesques that are presented on the news channels demonstrate the entertainment that the Malayali mindset strains out of dark humour.

It is, in fact, often pointed out that the Malayalis are the perfect audience that the cartooning industry can have, owing to their superiorly political, argumentative and contrarian outlooks. However, it is important to trade back to the budding years of political cartooning in Kerala if one is to attempt at understanding the present tendencies of Malayali political cartooning. According to E.P. Unny, Kerala owes its epitome of success in the cartooning industry to Ayyan Kali and Sree Narayana Guru, the two of the greatest early twentieth-century social reformers.

He says, “They gave the common man and the lower castes, who couldn’t even use words like salt in public, the courage to join public conversations. The teashop became the site of verbal humour, a lot of it political, and that translated easily into the visual humour of cartoons. That is where cartooning in Kerala acquired its intensity.” A.R Venkatachalapathy, a cultural and social historian, concluded while doing his research, that it was the politically stimulated ambience of Kerala that gave an edge to the cartooning tendencies of the state. He claimed while speaking to ‘Sahapedia’, “Cartooning requires audacity. You need to have a political vision. The political vision of Tamil cartoonists has never gone beyond accepted middle-class norms… I think Kerala has succeeded because of the strong Left tradition, which gives a theoretical arsenal to criticize. You should have a political vocabulary to criticize, which has been provided by Marxism which essentially is a very anti-status quo(ist) ideology.”

The most important factor behind the rise of political cartooning in Kerala was the binary, explosive and toxic nature of the state’s politics. Within seven years of attaining a democratic existence, the former state of Travancore-Cochin had been under five ministers. After being under the rule of a Leftist government for only three years in the later part of the 1950s, Kerala has been chiefly under the leadership of shaky and multifarious coalitions controlled either by an independent Congress or by the Leftist government. This has provided the Malayali cartoonists with the promising advantage of a persistent thread of inspiration –never-ending scandals, double-dealing, party hopping and factionalism.

As Unny pointed out in ‘Bhashaposhini’, “Neither Kerala’s politicians nor its cartoonists have had any rest since the birth of the state.”

The Voice Of The Versatile

While one of the major facets of cartooning in the Malayalam media industry is political cartooning, ‘Bobanum Moliyum’ was one cartoon series that gained high popularity among both adults and children alike and was launched in 1962. It traced the lives and the tiny world of two mischievous children, their small dog, and their quests in an archetypal village of Kerala. The series presented some stereotypical characters like the harassed mother, a suburban politician, a father who is also a lawyer, and a hippie called Appi.

Despite the stock characters, gentle but precise humour runs throughout the series. The weekly series was created by V.T Thomas and was published in the ‘Malayala Manorama’. The most surprising element of the series was that even though it was most popular for the antics of the children providing for a good laugh, there were touches of subtle political and social satire in a fictional world where village conspiracies, slogans and rallies were nothing outside the common.

It was around this time that G Aravindan created ‘Cheriya Manushyarum Valiya Lokavum’, a cartoon series that was published from 1961 to 1973 in ‘Matribhumi’. With this series, Aravindan aimed at attracting readers into the life of Ramu, an ordinary man who takes to observing the surrounding world closely.

However, one large void that seats at the heart of this fascinating world of humour, sketches and irony is that it is an industry that is largely and exclusively dominated by the male gaze and the men in Kerala. The jokes and humour found in the cartoons are mostly sexist and that is a problem that needs to acknowledge.

Addressing the urgency of this problem of gender bigotry, E.P Unny encourages, “When I go to talk to young school children on cartooning, the girls ask me: do women really look or behave like that? We need to find an answer to that.”