Albert Pinto – The Angry Young Indian Man

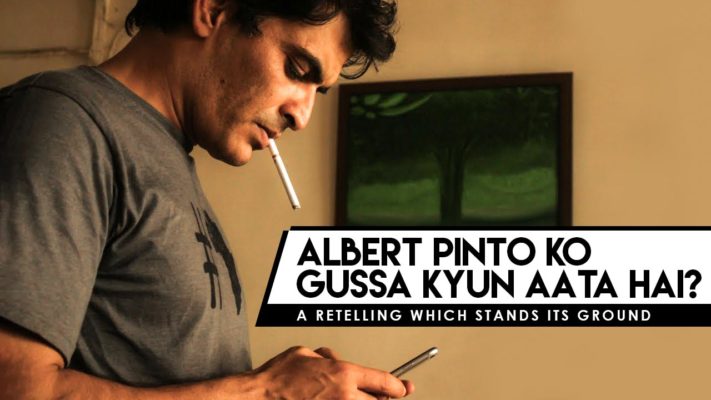

‘Albert Pinto Ko Gussa Kyon Aata Hain’ has been termed as a “conceptual remake” of the 1980 original film starring Smita Patil, Shabana Azmi, and Naseeruddin Shah by Soumitra Ranade, the writer and the director of the 2019 remake. In the latest version, Manav Kaul plays out the part of Albert Pinto, the angry young man. However, contrary to his character as depicted in the original version, Manav Kaul’s Pinto is an administrative worker as opposed to Naseeruddin Shah’s Pinto who was a car mechanic.

The 2019 Pinto’s illusions of idealism are crushed when he finds his virtuous father being wrongfully accused. The film puts to question the power of a common middle-class man who is angry, who neither wants to be the victim nor the one to sit and watch. Would he be able to extract corruption out of a system that is infected with vice? Despite having the hopes up, Ranade does not intend to provide an optimistic vein to the film. Instead, the film presents a frustrating sentiment of helplessness, of dishonesty and lack of integrity, a dystopian truth where the money is power.

The Past And The Present

Quite near the end of the 1980’s original version of the film, ‘Albert Pinto Ko Gussa Kyon Aata Hain’, Saeed Mirza had made sure to present a significant moment within the plot that echoed a shift in Pinto’s thinking. We find the car mechanic, Pinto, having lunch with his colleagues when he is called by a rich customer who is restless to have his work done at the instant. Previously, the film has shown Pinto sucking up to the same customer, but this time Pinto’s attitude bears a change. Pinto’s illusions about the glamour of the upper class, which he had long held on to have been shattered and Pinto refuses to attend to the customer before completing his lunch. Mirza hits with subtlety, in this particular scene, at the angry middle-class man’s protest towards the privileged advantages of the upper class.

In a similar point of transition in Ranade’s Pinto’s life, the food metaphor is again used. As Pinto moves across the kitchen of a highway dhaba to reach a sex worker, the film focuses, in slow motion with ominous music as the background, on an enormous knife cutting into chickens. Clearly, Ranade uses this scene as a clichéd metaphor for the ‘preying on the flesh’ idea. Briefly then, the differences between the well made original and the poorly executed remake are crystal clear. Even though Ranade had the support of the best performances from some of the best actors and a well equipped and edited film, his remake fails to hit the mark owing to an inconsistent script that does not quite begin its ascent.

An Eye For Detail: Who Does It Better?

As a director, one of the many strengths of Saeed Mirza was his incomparable ability to grasp the minute details of the lives of his characters. Besides making broad commentary on the Indian social scenario, Saeed made efforts to detail his characters with expertise. In the 1980s original, Saeed makes this highly evident through details like Pinto’s speech regarding the objectification of the Christian woman dressed in skirt and sunglasses, and the “public service announcement” in a cinema theatre that ultimately is revealed to be propaganda for owners of the textile factories. Mirza not only masters the trope of the “Angry Young Man”, but also criticizes it when he irreplaceably places Stella as the punching bag for Pinto to vent out his anger. Such little details are what gives Mirza’s original texture of the 1980’s social reality.

On the contrary, however, Ranade fails miserably as far as a detailed structure of the film is concerned. Despite Pinto’s administrative job and a few oddments of scattered English, both from Pinto and Nayar, the film does not literally identify anything that could anchor it to the present social context. Opposed to Mirza’s careful individualization of Pinto, Ranade loses Pinto’s identity, reality, and individuality within the void of his unformulated anger against “the system”. For example, in one particularly potential scene, Albert goes through a meltdown at a store and frequently asks the manager, “Do you want to buy me?”, implying that in the present world and society everyone has a price and more than often, that price is not too high. The scene comes across as weak and unpersuasive not because it lacks in the performance, but because it lacks context.

The Rights And The Wrongs

Director Ranade employs a secondary timeframe to shift us into Albert’s past illustrating the reason and the process of Albert changing from an agreeable person to a potential killer angered by corruption and apathy. In fact, at one point, Albert is heard saying, “It was as if a bulb had broken inside my stomach.” Ranade’s remake definitely gains points for the performances of highly acclaimed actors like Nandita Das, Manav Kaul, and Saurabh Shukla. They have left no stone unturned in delivering powerful performances as is usually seen from them. Nandita Das plays with expertise, the multiple characters that Pinto hallucinates in a state of fever, and each of these characters is equally convincing. Kaul’s performance is, as usual, compelling, and brings into effect a theatrical performance in an almost theatrical setting. He is adequate in taking the rage of Naseeruddin Shah’s 1980 Pinto and heightens his performance to suit the contextual scenario of 2019.

There are a few insights that are so deep that they do leave a mark on the audience. For example, Albert explains his austere view of the world to Stella when he says that there are three types of people living in the country. The first is the rich people who are like drunk drivers leading the country, the second is the poor people who are like dogs spending nights in the street and being run over every other night. Finally, there are the middle-class people who are like crows and scavengers looking for dead meat to gorge on. At this point, one is able to feel the rage rising in the guts when Albert cries out loud, “I don’t want to be a crow!”

However, this does not save Ranade from delivering a disaster. A grating background score and the unreliable script becomes the fall of the remake. Ranade’s use of essential devices like the hallucinations of Albert, the flashbacks, the conversations between the investigative officer and Albert’s family on his disappearance, all of these are presented in a worn out and almost exhausting tradition. Given to the fact that having a classic source had Ranade’s work mostly cut out for him, Ranade could not use it to his advantage. Owing to the original source and the powerful performances, Ranade’s remake could have made its mark had it not been for the script and the direction. The audience’s appropriate response to the film should be expected to be as confused as Nayar when he tells Pinto during a road trip, “Teri kahaani mujhe samajh mein nahi aayi (Your story doesn’t add up for me).”