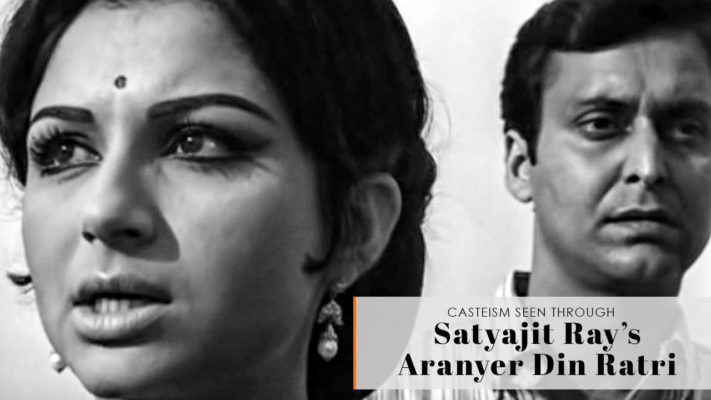

In The Wake Of Recent Casteist Crimes, The Legacy Of Aranyer Din Ratri Is Significant

Caste as a functional social custodian is so finely delineated by Satyajit Ray’s Aranyer Din Ratri (1970) that even almost after 50 years of its release, we hold a body of work as pertinent as ever in a reality where we lose Rohit Vemulas and Payal Tadvis to institutionalized caste atrocities. The film remains underrated in its subtle treatment of caste hierarchy.

The Urdu word “Fitraat” is apt to describe the evil that is inherent in professions pre-determined by caste. In the microcosm of Aranyer Din Ratri (Days and Nights in the Forests), the pecking order allows an upper-caste gentleman can forcefully take a Santhal woman for a prostitute. In the 21st century AI dominated India, it results in mob lynching, rape, manual scavenging, honor killings and bullying in eminent educational institutions. Casteism is observed and kept alive almost in religious fervor and its abeyance is considered to be immoral, against dharma.

Ray’s film talks about the placid assumption of power by the four upper-caste men over the marginalized tribal people. These men subject the Santhals to physical abuse, almost entirely robbing them of their day jobs. As the nation sighs at recent caste-based violence- the death of Dr. Payal Tadvi, the film nudges us to look at the layered functioning of casteism the contemporary society feels compelled to conceal under sophistry.

The Unaccustomed Earth Of Casteist Bihar

Days and Nights in the Forests, originally written by Sunil Gangopadhyaya, is set in Bihar where casteism happens to be a major vote bank policy. It also happens to be the state with approximately 130 EBCs (Extremely Backward Classes). To many, the film remains a harrowing experience of upper-caste, middle-class Bengali city dwellers’ whims and fury tainted by raw sexual violence. The chiaroscuro effect on four male characters Ashim, Hari, Sanjoy and Shekhar, parading in their city-bred chauvinism, is poignant, and especially when we assess how casteist slurs still persist at the cost of human lives. The violence is accentuated by manifold as authorities nonchalantly deny any knowledge of it and proudly claim India to be a casteles society.

Ray has austerely us how caste has settled into the complacency of everyday lives breeding ignorance, amnesia, and denial only the privileged can afford. How caste has kept an undeniable chunk of minorities on the edge? Even after decades of its first publication and witnessing major political turnarounds, Days and Nights in the Forests admirably gives us a few answers to this question.

A Film Dear To Modern India

Hari’s liaison with Duli, the Santhal woman, sparks off a debate on male gaze fixated on a woman who is both socially and economically inferior to the former; this woman is mercilessly objectified by Hari’s friends and viewed solely in her identity as an exotic “other” amongst them. This authority is further accentuated by using Duli as a prostitute, enticing her to provide sexual favors in exchange for money. The language of manoeuvre is explicit, a language which exemplifies Hari’s social status and his refusal to acknowledge Duli as a peer. This same language has penetrated into different social institutions where the dominant has a hereditary right to mock their “socially inferiors”.

The legacy of persecution is survived by authorities who hardly thought it necessary to form a committee qualified to undo institutionalized casteism. Even to right the wrong, the village chowkidar in Days and Nights in the Forests is dependent on his whimsical, socially superior “babu” a word that historically labelled an egocentric, self-absorbed master. The terms reigned in extravagance during the zamindari system and much after it. British Raj might have done away with zamindari and its centralization of wealth, but are the century-old inequities really unheard in 4G India?

Class, Conflict, And Casteism

Ray’s classic elucidated on “Bengali Bourgeoisie” from early on to help us recognize the sins of class complacency. This suave complacency is directly proportional to the men’s casual misogyny and general assumption of their assured right to dominate on human bodies. The men could not simply wrap their head around their misdoings and misdemeanor fueled by passion and contributed to all forms of possible discriminations within their immediate surroundings. Casteism in India is amplified by this clear demarcation between upper-caste affluent characters and lesser-privileged sections and the unjustifiable tyranny of the former over the latter.

Caste consciousness is unmediated in metropolis, villages, and valleys alike. It goes beyond routine crimes and manifests itself in offensive acts like land encroachment or abuse by lower caste village council heads. In the film, the men’s easy targets become people who belong to the absolute lower strata, with perhaps zero possibilities of upward mobility.

Smriti Sharma, Delhi School of Economics, articulates that casteist crimes were aimed at material gratification from those victims who are comparatively well off. Even at the root of the most nonchalant hate crimes or casteist slurs, remain buried deep, envy and the intention to emotionally cripple the victim. Satyajit Ray lashed out at innate caste prejudices and sense of entitlement, alive and robust across different working class divisions. The evils of this system have seeped into the lives of disenfranchised classes, paralyzing economic growth and prosperity generation after generation.