A Vague Understanding Of Kabir Singh Chowdhry’s Mehsampur…

The first word that would pop-up in your mind when you watch this headily genre-mixing film, Mehsampur is perhaps Obscure. Mehsampur already a veteran of many film festivals across the globes, is about nothing and everything. In that, it refuses to be categorized into a pondering fare most often experienced in European Auteur movies, nor does it sit idly in the documentarian retelling of a bygone story. If one has to find comfort in definitive allocation, then Mehsampur is a fictional story told through non-fictional elements in a fantastical manner. And so, the film is a meditative experiment of characters obsessed not only by their own goals, aspirations and worlds, but in equal measures those of people they cross paths with. As the tongue-in-cheek disclaimer at the start movie says – Any resemblance to actual events, to persons living or dead, is not unintentional, the movie stays true to its word.

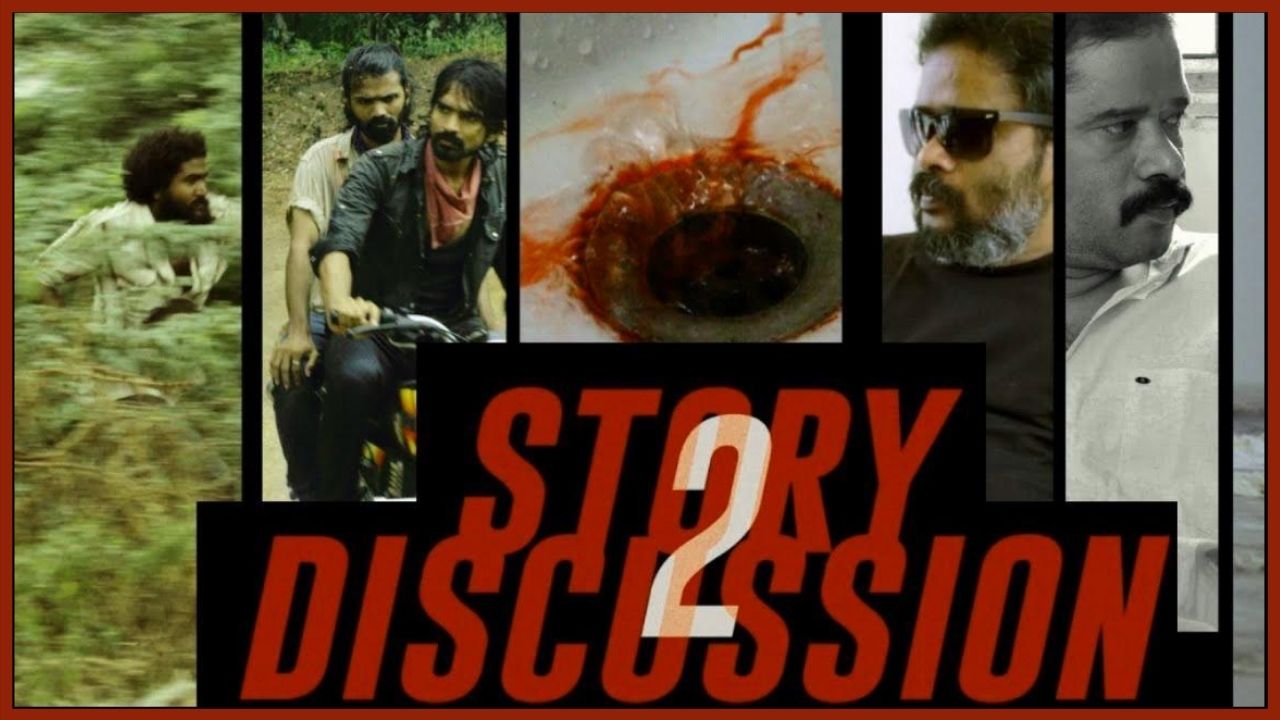

Mehsampur starts with an aspiring film maker, Devrat Joshi, who lands up at Ludhiana to research, document and produce a film on the untimely and mysterious murders of the ragingly popular local singers duo – Chamkila & Amarjot, who at the pinnacle of their careers were invited to perform in places like Dubai and Canada as well. Unfortunately, the singers who enjoyed cultish fan following much owed to their sexually provocative songs, were gunned down by unknown assailants in the late 80’s; Chamkila was merely 27 years old when he died.

Their death is still shrouded in mystery and has become a subject matter of the production of more than half a dozen movies and a few documentaries. Although none of them have seen the light of the day, given the simmering sentiment veiled over the deaths, they still continue to lure filmmakers to try their hand at dealing with the subject. We are made privy to one such attempt by Mumbai based filmmaker Devrat, who is seen wandering about in Ludhiana, clutching his handicam and narcissistically exploiting his subjects of research. Devrat is not content in being a mere documentarian, who absorbs the information around him or who wants to excavate the truth behind his topic of discussion. Rather, he is obsessed with his camera angles, reenactments, scenic compositions and scripted dialogues, forcing the people he is interviewing to mouth them, and more appallingly asking them to conduct themselves in a certain manner that he deems fit.

Story Within A Story…

His first interview interaction within the movie comes with Kesar Singh Tikka (who ‘plays’ himself in the feature) the fiendish drunken man who used to be the manager for Chamkila-Amarjot, until he was unceremoniously left out from the troupe. Devrat makes Kesar enact a few scenes, over and over again, meticulously measuring the impact of such scene, almost as if making a non-fictional feature. Then comes Surinder Sonia (playing herself) a yesteryear singer and love interest of Chamkila, who is eerily still stuck on her foregone fame and beauty, uncomfortably flirting with Devrat and imposing her whims upon him.

Eventually, Devrat realizes that these points of view towards the overall story are both slow and irrelevant. This lack of promise frustrates Devrat to the core as he starts frequenting a bar, furious at himself and angered at another film crews who are popping up at the same area intending to make a movie on Chamkila-Amanjot. At the bar, we meet Manpreet (played by Navjot Randhawa) the only rare fictional character apart from the protagonist and the Jagjeet Sandhu’s jolly bar singer, who shamelessly croons desi versions of western retro-pop hits. Apart from these fictional undertakings, interestingly every other character is played by real people, in the actual capacities of their involvement in the lives of the singer duo.

The Sudden Shifts Of Narrative Objectives…

Devrat and Manpreet connect over a few drinks and end up spending the night together cajoling each other in trippy dreams and crumbling into each other’s naked bodies. Manpreet, as it were, is an actress looking for an opportunity to work and seeks out Devrat to be a part of his ‘documentary’ never truly understanding the twisted mechanisms at play. As Devrat decides on casting Manpreet to play Amanjot; the wistfully neurotic Manpreet starts getting obsessed by the character, twitching, twirling and running away into the woods almost as if possessed by a ghastly spirit.

Along the way, Devrat also finds another essential member of the singer’s troupe, a Dholak Master by name, Lal Chand. Lal Chand on the edge of financial crises, agrees to help Devrat by coming along with him to Mehsampur, where Chamkila-Amanjot were killed. As the trio, Devrat, Manpreet and Lal Chand, arrive at Mehsampur, the movie jerkily shifts gears from being a documentary intended feature, to an absurdly drug induced hallucination. The movie ends on a disturbingly macabre note, which overturns the whole premise of Mehsampur, revealing in the fleeting final shots the cost of mad obsessions.

Mehsampur thus is a surgical tear out from the usual genre films. The maker of the film, Kabir Singh Chowdhry via his obsessed and exploitative protagonist, wants to lay bare the façade of documentarians, who on the pretext of capturing reality, more often than not, end up capturing moments according to their liking and narrative. Theirs’s is a convenient and scripted truth, designed to enthrall and engage its viewers than to build a thesis. It’s all a palatable representation, and in so Mehsampur comments that anything which is processed onto a film-screen, is meant to be inherently subjective.

In a meta-reflective standpoint, Mehsampur tends to underscore a thematic about deeply flawed men who tend to find warmth in resorting in abuse in the name of creative process. Creativity becomes an umbrella, in the shade of which abuse prospers. And so, Mehsampur becomes a psychological procedural to understand that nothing amounts to anything and vice-versa. The film itself is not to be sought for its storylines, but for its detachedly weird telling of a ‘non-story’. Like Negative Space, the film is a remainder of thoughts, rather than an active pursuit of objectives. Mehsampur is in such context becomes anti-matter, or rather an anti-film, which will in time accumulate its own ethical and moral dust, to become a genre in itself.