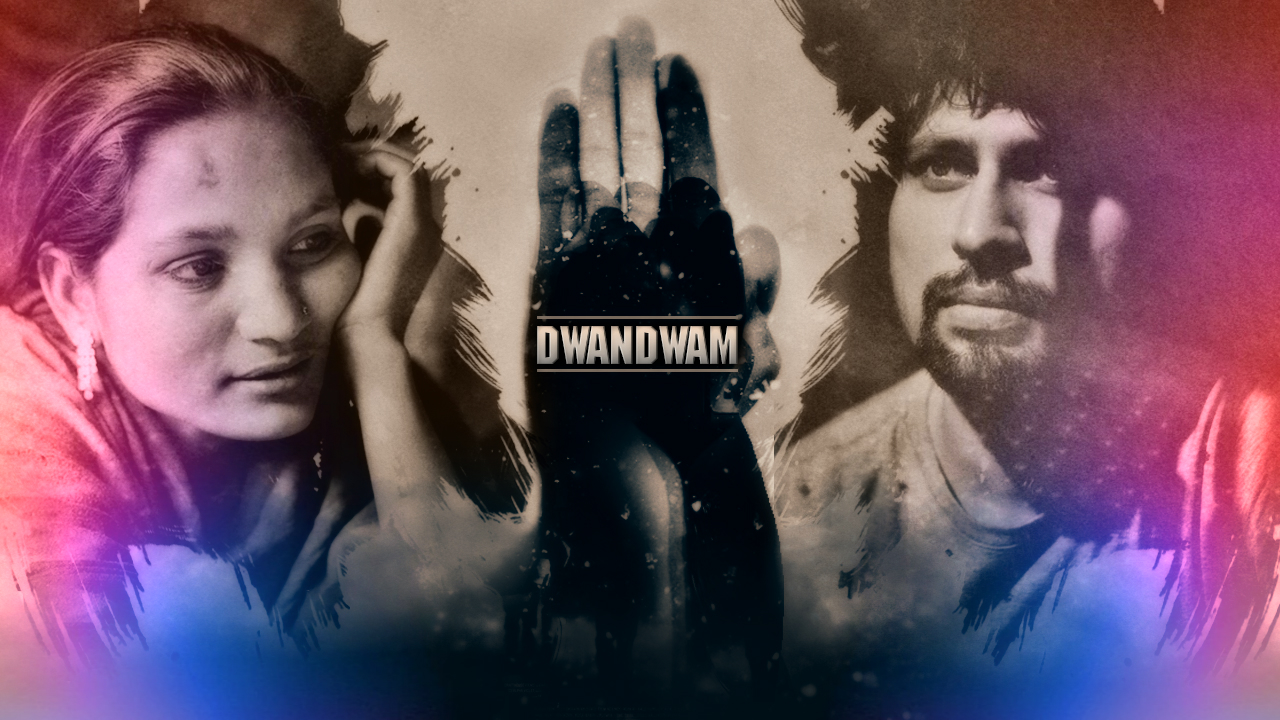

Duology Of Drama – The Paradox Of Dwandwam

What makes a movie great? As a neutral movie watcher, or should I say, content viewer across platforms, this question has always baffled me. Again this pondering is not limited to just films. It is equally applicable to every performing art. A theatre play, a short-feature, a standup special, a documentary, or for that matter even a Vlog or a Meme (dare I include them in the same breath), always raises this question in my neural setup. What are those few factors which make me sit up, take notice, and connect with them at various levels of psychological joy?

A few of my academic friends, who are kind enough to indulge my pondering, albeit in a state of higher consciousness (pun intended), generously, and might I add very patiently, go on to explain at length as to what makes for a great performance or a movie. Some suggest that it is the way a story is told, and some adamantly say it is the essence of the story itself. Some go out a limb and blurt out that it’s the way the actors enact it, or the rousing music which makes you live a life along the feature, without actually living it. Some of them tripping on philosophical hooplahs often tell me that it is the ease by which a feature makes you escape reality, that makes you truly engage with it. Afterall, art is perhaps a tree of escapism rooted in realism, from which one enjoy the delicious fruits. Sometimes I think all these factors, in a cumulative manner, make for a deeply enjoyable, cerebrally sumptuous feature. One such feature which makes for a wonderful conglomeration of such ideas is an Indie feature called Dwandwam.

The Story Of Dwandwam – The Complications Of Life

Helmed by a new director Aditya SriGupta from Bangalore, Dwandwam poignantly speaks about the dualism which exists inside every one of us. And more so, in the context of an artsy populace. The film subtly raises the question of personality dualism which speaks towards, challenges, and compliments the contrasting nature of a human artist and the artist in the human. Sree (Lakshmi Keripoli) plays a prostitute who is rescued from the clutches of a Hotel Manager molesting her, ironically right after she comes out of a room after spending the night with a customer. Yonir (Gopi Kumar) who happens to be at the right time, and at arguably at the right place that fateful morning, observes the molestation and ensures that Sree is rescued from the pangs of business and inhuman treatment. As it so happens, Sree is then taken to a rescue foundation but fails to adjust to the life of it. Here in starts our discussion of dualism, the Dwandwam. Here is a woman, a prostitute, who has known the hardships, the pleasures, the luxuries and the curses of selling her body for more than a decade now.

Normalcy in life, the ever ambiguous revenue flow, the perfect imbalance between hard work and salaries are concepts which are alien to her. To a woman who knows not how commerce and economics work normally, and who is perhaps been seen, treated and internally accepted as a product of barter, how does the economic buffoonery of our country work out?

The Conundrum Of Story And StoryTelling…

In the questions asked, particularly the conundrum of duality, Aditya SriGupta, holds a mirror to what we are and what we aspire to be? Are we truly rescuing someone when the promise of paradise lurks in a shadow of hell? Is our world actually better for people to come to or is it worse enough to escape from? Sree, although burdened by this confusion, accepts the fact that she needs to fit in with the society, despite a million questions left unanswered. The duality of existence, with more questions than answers, therefore begins for Sree.

As we move forward with the movie, we understand that Yonir, someone who exudes a radiance of a creative awareness. Yonir is a self-acclaimed painter, who in his own words “Wants to die as soon as he makes his masterpiece, to avoid his mind to corrupt him with any other idea”.

Yonir, under the shrug of self-motivation and self-proclamation, is a digital artist who is struggling to make ends meet. Again the sense of Duality persists, as the life he wants and the life he portrays he wants are two very different stories. As time passes, Yonir crosses paths with Sree, and they decide to live together. Both, as it would seem, are progressive conformists, who want to lead their life independently, while living together. Needless to say, the core ideology of the film is reflected here as well. As the story unfolds, Sree becomes the muse for Yonir, as he starts making his masterpiece. But all is not well when Sree is diagnosed with a rare cervical disease, which disallows her from sitting still for more than five minutes at a stretch.

The questions which are slowly, subtly and poignantly answered over the film’s runtime are broadly these – How does a painter make a nude painting when the subject is not static? On the other hand, does a masterpiece by any artist, require an ultimate sacrifice? How far will you go to bring to life something spectacular? What do you do when the hand that saves you, asks you to give up your life? And most importantly, where do the shades of humanity and artistry intercross. And what happens, when it comes to a point of choosing between love for a person and love for art, between being abstract and being a purist, between life forgone and life to be. These questions wound up the whole story arch, in an interlacing thought processes which are hard to shake off even after you walk away from the screening.

What Makes The Movie Actually Leave You Stunned?

First off let me draw out the obvious errors, mistakes and flaws inherent to our traditional and contemporary movies, which Dwandwam radically ignores. To start off, there is no star son or nepotism seething into this movie. Why do I mention that so particularly? Well, nepotism and tokenism is something which has made our art of filmmaking highly regressive. Consider this, bring me a star-son who will be ok, portraying a troubled human, who is weaker, both morally and psychologically, than the sum of all characters in the movie. Bring me a star-son, who after stripping out his riches, and his family lineage can actually act and perform. Bring me a star-son, who is willing to give up his privilege, right here right now, and then we’ll talk. And thus the rant goes on. So coming back to Dwandwam, the story is the driving force of this movie. Sadly, that is not a setup in which any self-respecting privileged actor would act. And thus, the role of Yonir is played with gripping intensity by Gopi Kumar, a respectable name in the theatre circuit of Bangalore. What a ridiculous place to pick up an actor, wouldn’t you say? To add to that audacity, even Lakshmi Keripoli comes from a theatre background. I mean they actually act with passion and all, but it is an all but sure situation that this will be their first and last film. Art is a business, and business always requires glamour. Come to think of it, why shouldn’t nepotism exist? Afterall, the star dad’s produce the movies, some even distribute them, which feature their kids. There’s business everywhere, employment as well, they are doing so much good to the society we live in. Hence, the dichotomy of Dwandwam. It challenges you in ways of thinking that is seldom seen on silver screen.

The Perfect Story Adaptation…

Another factor that Dwandwam manages to pull off, quite spectacularly so, it comes gloriously close to being an auteur film in itself. The story (also by Aditya SriGupta) is perfectly translated onto the screen, and there are no compromises even in his thought process. To a layman, who accommodates a limited understanding of storytelling, this line “compromising a thought” might not actually mean anything. But to someone who deeply understands and joyfully revels in the intricacies of storytelling, the line is as deep as an ocean. You see, with the case in hand, “compromising a thought”, is a moral binding upon a creative process. Again an irony. When we say that we are creative people, do we even understand that we are as creative as the society and situations around us, allow us to be? And therefore, we are not exactly creators, but just good mimickers of products already existing and created. That is where Dwandwam excels at. It doesn’t adhere to any rulebook of creativity. There are long shots, which are meaningless, for example, a scene where Sree, after being rescued, eats a whole lunch.

There is no meaning to it. There is no urgency in it either. What does the scene actually achieve? Nothing. It just shows a woman who is having her lunch. There is utterly no need to dissect that scene to parallel some thought. But then, our minds, who have been trained to absorb a story quickly, almost grab and chew it off within minutes, can’t comprehend that life is actually slow, terribly slow. Now the question is why would we be watching a movie if all we were shown was real life? The slowness, the non-happenings, the disconnected karma, all these things we all live day in and day out. Then why see a movie for that? Well, because it’s a story told at a pace that you can live it through. And thus, it requires a solid grip on subject material by the filmmaker, to actually take that risk of inserting something that neither is relevant or logical. I wonder as to How many of us, the so-called creative minds and storytellers, can actually be as patient and as luxurious in our pacing as Dwandwam is.

Going Beyond The Pretense Of Being Voyeuristic

As we dissect the movie Dwandwam, on its nature of Dualism, or in a traditional manner Duality, we are often left questioning more than getting the answers. One of this aspect is subconsciously achieved by cinematography and music. Cinematography by Joseph Emmanuel is impatient, close and intimate. These words popped up in mind as I went through the film’s absorbing 140 minutes of runtime. When does Cinematography, as aforementioned, become Impatient? Well, it is when the camera is dynamic and restless to tell a story, where in fact, the movie is taking its own pace.

In many ways, the camera work actually reflects our frustration with the movie, which leaves no stone unturned to make us uncomfortable. The maker of the movie doesn’t adhere to the usual lighting that enhances the roles being portrayed, there are no gaudy looking backgrounds, no slow pan shots of love or emotions, no pretence in doing something poetic, and there are no trappings of being visually stunning. I suppose that’s what makes the cinematography, as I mentioned before, deeply personal. The shots do not define a story, but the story defines the shots and the mind behind it. There is no ridiculous need to put a camera under the thigh of a lady to show seduction, or within a burning furnace to show an action, or outside a window to show the depth of a character, nothing is traditional. Does that leave ample creative satisfaction for the cinematographer? Well, your guess is as good as mine.

The Music Which Deepens The Soul

The music, as you might be expecting (and perhaps branding the movie as a voyeuristic art feature), is minimal. Essential to the packaging, but not the packaging itself. There are no thumping beats, neither the show-off of deep bass involvement and of course, there are no songs. To put that into a perspective, the movie itself has no trailer. The show makers might’ve believed that the movie would grow by itself, and perhaps their musings, much like the protagonist of the movie, are on something vaguely termed as “pure creation”. The music transcends the scenes to different highs and lows, never ever being static or selfish. Yup, the music could always be selfish, when the composer inculcates the story unto himself and starts composing music in the way he deems fit. Dwandwam in this aspect, asks of the music composer, to make music based on the story essence and not the screenplay. And it is quite clearly established, in long shots of just cricket chirping, that music is not the hero here. If the musician wants to celebrate his art, his calling needs to be in concerts, individual shows or collaborations. But here, and it is very clear, the music needs to enhance the whole feature presentation, not reduce it to a routine.

The Trappings Of A Movie – A New Wave Of Realism

Now since we’ve taken the technical aspects onto the grind, each one of us is truly impressed, at the end of the day by the manner in which a story is played out to our understanding by the actors. Gopi Kumar and Lakshmi playing the lead actors (a rare conformity to the adherence to the usual filmmaking), have zero inhibitions in playing what they mean in the story. Not the roles, but their individual stories. Roles are such restrictive terminology; don’t you think? Someone is cast as someone. Or the role best fits a star? Who said so. Do you mean to say that some roles are written while having a star in mind? How does that work? Movie writers baffle me sometimes. They are capable of including ‘commercial elements’ in their artwork. So a writer, for the moment of eternity, is a writer isn’t it? He tells a story of his heart wishes and minds works. What now are the ‘commercial elements’? It is beyond me to understand how these play out? Gravity-defying fight sequences, external moral dilemmas, women falling for the men because basing on their machismo, or fight sequences which have no earthly meaning, are all absent. Of course, the list also includes apprehensive touching, indecisive nature, and other nitty-gritty of romantic escapades. Pretense you see seems a cuss word within this project.

So where does this leave us? Dwandwam, as a movie, does it truly appeal to everyone? Does the film change anything? Will it come across as a definition of movie making where we finally accept our regressive storytelling techniques, as ancient and regressive?

We certainly hope so, when hopefully, this movie gets finally made someday, because no one dared to make it yet.

Or perhaps, it will still stay as a hopeful story that an absurd filmmaker is still roaming around the streets of filmnagar, pitching it for the last seven years to all the major studios, to a point where he meets us in a small chai shop here near our office.